By Dr Tuğba Deniz (İstanbul University – Cerrahpaşa)

Communities in Türkiye’s remote mountainous regions grapple with a myriad of environmental, economic, and social challenges. Among these challenges, erosion stands out as a significant concern. While it initially seems like a purely environmental problem, its long-term ramifications extend to both economic and social spheres. This blog provides and overview of the erosion challenges in Türkiye’s mountainous regions and illustrates how soil erosion and flooding caused by deforestation can be counteracted by public intervention by reference to the “Erosion Control Project” for the Çakıt Stream Watershed in southern Türkiye.

Erosion refers to the abrasion of soil and its movement from one place to another, and it remains a primary cause of soil loss worldwide. Erosion can stem from two primary sources: (1) natural structures such as climate, topography, geological structure, or soil sensitivity, and (2) social and economic factors which include deforestation, inappropriate or excessive agricultural practices, overgrazing in pastures, and unplanned or irregular rural settlement (Bahtiyar, 2003; Günay, 2008).

As erosion disperses organic matter, it severely diminishes an area’s soil productivity. Soil productivity, defined as the capacity of soil to sustain agricultural crops or other plants and structures using a defined set of management practices, is critical. Erosion not only affects agricultural yield but also poses risks to structures like natural dams. These dams, formed by debris flows, glacial moraines, or volcanic materials, can be weakened by erosion. Over time, erosion can destabilise these dams, leading to potential collapses and resulting in downstream flooding, substantial property damage, and endangering lives.

Uncovering Erosion in Türkiye

Türkiye’s mountainous geography is a result of its unique geomorphological features, which have given rise to diverse natural environments, notably in terms of plant endemism. Plant endemism refers to the phenomenon by which a particular plant species is native and exclusive to a specific geographic region or habitat. For example, the mountainous ecosystems of Türkiye’s Taurus and Black Sea Mountains are home to diverse vegetation, from forests to meadows and shrubs, all adapted to varying climatic conditions. The Taurus Mountains, in particular, are globally recognised biodiversity hotspots, offering ample opportunities for ecotourism, recreation, and grazing. However, in recent times, there has been growing demand for transhumance and mountain and winter sports. The resulting increase in construction and transportation infrastructure is exerting pressure on these delicate mountain ecosystems (General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, 2019). For instance, while the Taurus Mountains are susceptible to floods, primarily due to a mix of sudden heavy rainfall and large amounts of snow melt, deforestation remains a major underlying cause.

A view from within the Taurus Mountains, Türkiye (Şafak Omaç, 2022)

Indeed, Türkiye, as a whole, is susceptible to erosion and flooding due to its unique geographical location, topography, climate, and soil characteristics. Approximately 40% of Türkiye’s soil depth ranges from 0 to 20 cm, while about 2% of its land is unsuitable for plant growth because of issues with alkalinity and salinity. The country’s mountains, located to the north and south, elevate the country’s average altitude to 1,132 metres, which is notably higher than Europe’s average of 330 metres. Roughly 79% of Türkiye’s land consistes of steep slopes. The country’s loose soil types, combined with frequent heavy rainfall and flooding, make it especially vulnerable to weathering and erosion (Çakıroğlu, 2010). Given these conditions, around 75% of the land in Türkiye faces severe erosion. Specifically, erosion affects 59% of its agricultural areas, 64% of its pastures, and 54% of its forests (General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, 2019). Given the various types and severities of erosion found throughout the country, some studies have refererred to Türkiye as an erosion museum (Günay, 2008).

Scaling New Heights in Erosion Control: Past Successes & Current Practices

Natural resources can play a vital role in combatting erosion. Forests, for example, protect and improve the quantity and quality of water in the basins where they are found. Essentially, they aid in water replenishment and reduce erosion. Within and above these basins, forests capture rainfall, preventing rapid runoff and reducing the potential for it to become leachate as it passes over the soil. This process not only improves both the quality of the soil and groundwater health, but also contributes to the production of clean, fresh water.

Leachate is a liquid that results from water draining through a substance, often soil or waste material, carrying with it various dissolved or suspended substances.

In the 1970’s, Türkiye experienced soil erosion dispersing nearly 500 million tons of soil annually. However, afforestation, erosion control, and various improvement works – such as rehabilitating degraded forest areas, improving pastures, regulating grazing, and implementing advanced irrigation technologies in agricultural areas – reduced this figure to 140 million tons per year by 2020. According to an erosion prediction model and monitoring system developed by the General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, Türkiye aims to further reduce this number to 130 million tons per year by the end of 2023 (General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, 2019). As part of these efforts, erosion control initiatives are underway not only to mitigate erosion, but also to minimise its detrimental effects, ultimately enriching the impacted regions in ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

The Çakıt Stream Watershed, Türkiye (Şafak Omaç, 2022)

The Çakıt Stream Watershed, Türkiye (Tuğba Deniz, 2011)

The Benefits of Erosion Control in a Mountainous Watershed: A Case Study from the South of Türkiye

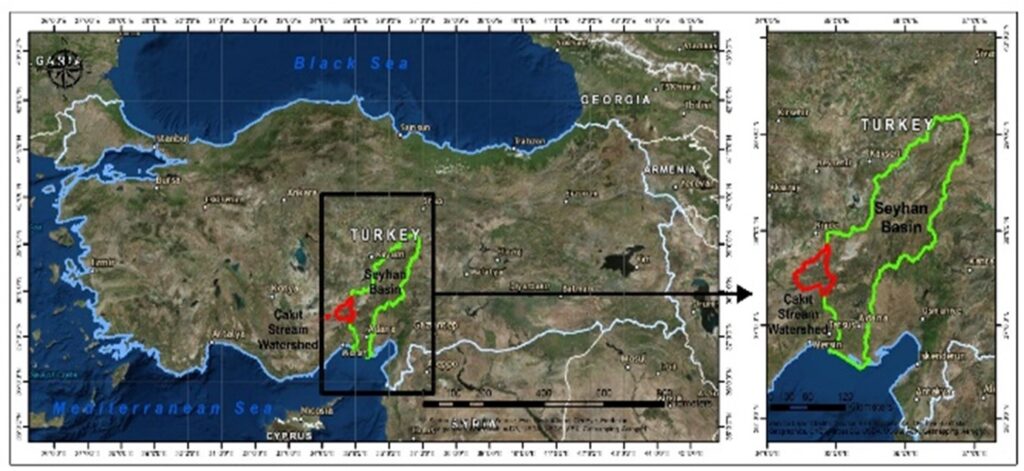

Numerous erosion control projects have been undertaken in Türkiye to counteract the erosion caused by deforestation. One notable project is the “Erosion Control Project” for the Çakıt Stream Watershed, which focuses on a sub-watershed within the Seyhan Basin in southern Türkiye, spanning the Adana and Niğde provinces.

The location of the Çakıt Stream Watershed (Deniz et al. 2020)

Forests of fir, red pine, black pine, and cedar forests cover 24,673 hectares on the steep slopes of these mountains. The Çakıt Stream Watershed exhibits typical high mountain characteristics, marked by high altitudes, steep terrains, extreme weather conditions, and distinct flora and fauna. Medetsiz Hill, at an elevantion of 3,542 metres, is the watershed’s highest point, while the Sürekçin Strait stands as the lowest at 724 metres. On average, the watershed’s elevation is around 1,600 metres (General Directorate of Forestry, 1988).

Before initiating the project, the watershed faced challenges such as erosion and flooding. These issues adversely affected livestock, forestry, agriculture, infrastructre, and the socio-economic well-being of the region (Kural, 1997). In the spring of 1980, the Çakıt Stream, a branch of the Seyhan River flowing into the Seyhan Dam, experienced an overflow. This led to floods that endangered the frequently-used E-5 highway, the Seyhan Dam, and other branches of the Seyhan River, and damaged the nearby railway network (General Directorate of Forestry, 1988).

The Çakıt Stream and its watershed (Tuğba Deniz, 2011)

With backing from the World Bank, the General Directorate of Forestry initiated the Çakıt Stream Erosion Control Project in 1982. This initiative aimed to combat erosion resulting from human-induced deforestation. The main objectives of the Çakıt Project include

- Protecting residential and agricultural areas from floods,

- Preventing sediment accumulation in the Seyhan Dam,

- Securing roads and railway systems,

- Countering soil erosion and preventing emigration from villages in the basin to cities.

A view of erosion control works in the Çakıt Stream Watershed (Tuğba Deniz, 2011).

To implement erosion control and related activities, 2,000 local workers from villages within the watershed were employed for 6-7 months annually over a five-year period. The works carried out within the scope of the project fall into four categories (General Directorate of Forestry, 1988):

- Slope land works (i.e., terracing, afforestation, grazing, slope stabilisation etc.)

- Rangeland rehabilitation works

- Food aid

- Employment support

Thanks to the project’s efforts, risks associated with flooding and soil erosion in the watershed have been considerably reduced. Sediment build-up in the dam has lessened, and the occurrences of rock and stone slides on highways are now more effectively managed.

Peak Value: Understanding the Value of Mountain Watershed Management

Both market and non-market goods and services (such as timber and recreation, and recreation, water production and purification, soil protection, visual landscape value, and biodiversity respectively) emerge from erosion control activities. Assessing the value of these non-market goods and associated forest ecosystem services necessitates rigoruous independent scrutiny to ensure the sustainable and efficient management of forest resources. This evaluation underpins the development of strategies, programmes, and project alternatives to forestry activities. It also informs land allocation, investment decisions, and financing priorities.

MARGISTAR’s Dr Tuğba Deniz delved into this subject during her PhD research (2012), focusing on individual’s willingness to pay (WTP) for benefits derived from forests and erosion control in the Çakıt Stream Watershed. Specifically, she examined WTP for flood prevention, soil erosion mitigation, dam longevity, and improved access to spring water. The findings reveal a positive WTP among the watershed’s residents for measures that prevent soil erosion and flooding, and enhance spring water access. However, there was a negative inclination towards prolonging the lifespan of the dam. The annual marginal WTPs per household, based on 2012 pricing, is detailed as follows:

- US$2.4 to diminish soil erosion by 1%

- US$1.2 to increase access to spring water by 1%,

- US$0.6 to delay flood occurrences by one year,

- and -US$0.1 to increase the dam’s lifespan by one year.

While valuation studies and their associated results are tailored to specific watersheds, such studies are criticial within the context of mountain watershed management. They help quantify the economic and ecological significance of fragile mountain forest ecosystems, shedding light on the the monetary advantages of maintaining mountain watersheds. This includes water provision, purification, and flood control. They also play a pivotal role in justifying investments geared towards conservation and sustainable forest management, ensuring the long-term preservation of essential resources that serve both local and downstream communities.

In sum, erosion can contribute to an area’s status as marginalised as it may result in periphery traps (e.g., emigration, inability to benefit equally from resources, etc.). Finding transformation pathways to combat such inequalities in mountainous areas is the main emphasis of MARGISTAR, which is why erosion and its ecological and socioeconomic consequences must be considered when planning ecosystem and policy action. Most importantly, this must take place with the participation of an area’s inhabitants to ensure that erosion control is carried out effectively and with minimised conflict potential.

The header image depicts the Taurus mountains and was sourced from Niğde Provincial Directorate of Environment and Forestry, 2011.

References

Bahtiyar, M. 2003, Toprak Erozyonu, Oluşumu ve Nedenleri, Erozyonla Mücadele TEMA Eğitim Semineri Notları, TEMA Vakfı Yayınları No: 26. ISBN: 975-7169-20-X.

Çakıroğlu, İ. 2010, Sel ve Taşkınları Önlemede Yukarı Havzalarda Yapılan Erozyon Kontrolü Çalışmalarının Önemi ve Çevre ve Orman Bakanlığı Ağaçlandırma ve Erozyon Kontrolü Genel Müdürlüğünce Yapılan Uygulamalar, II. Ulusal Taşkın Sempozyumu Tebliğler Kitabı, s: 533-543, 22-24 Mart 2010, Afyonkarahisar.

Deniz, T. 2012. Erozyon Kontrolü Çalışmalarında Değer Analizi (Valuation Analysis in Erosion Control Activities), İstanbul Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İstanbul.

Deniz, T., Giergiczny, M., Riera, P., Ok, K., 2020. Comparison of the Models in Choice Experiments Method Application for Watershed Afforestation in Southern Turkey. Kastamonu University Journal of Forestry Faculty, vol.20, no.3, 243-254.

Günay, T. 2008, Orman, Ormansızlaşma, Toprak, Erozyon, TEMA Vakfı Yayınları, Yayın No:1, ISBN: 978-7169-05-5, İstanbul.

General Directorate of Forestry, 1988. Adana Çakıt Çayı Erozyon Kontrol Projesi, Ministry of Agriculture and Forest, Afforestation and Silviculture Department, General Directorate of Forestry Application Projects, No: 2, Ankara.

General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, 2019. National Strategy and Action Plan to Combat Desertification 2019-2030, The publication of General Directorate of Combating Desertification and Erosion, Ankara.

Kural, S. 1997, Havza Yönetimi ve Çakıt Projesi Örneğinde Uygulamaların İrdelenmesi, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Çukurova Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Peyzaj Mimarlığı Anabilim Dalı, Adana.