By Igor Ponjiger (Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia), Tamara Jovanović (Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia), and Ilija Djordjevic (Institute of Forestry, Serbia)

Serbia’s tourism sector, traditionally focused around major cities, is increasingly highlighting its mountainous regions. These areas are becoming prominent tourism hubs due to their natural beauty and opportunities for activities such as hiking, skiing, and ecotourism. The rich natural resources in these regions support various outdoor activities, including hunting. Find out how mountain tourism, alongside spa and wellness tourism, plays a crucial role in Serbia’s overall tourism development, helping diversify rural livelihoods and improve local economic conditions.

From the Pannonian Hills in the north to Montenegro, Albania, and Macedonia bordering the country in the south, Serbia’s landscape is dominated by mountains. These mountains form parts of the Balkan, Carpathian, and Dinaric ranges and feature Zlatibor, Kopaonik, Divčibare, Tara, Stara Planina, and Fruška Gora – some of the most visited mountains in Serbia.

The tourism sector in Serbia primarily focuses on business trips and short break trips to the capital city of Belgrade, Novi Sad, and Niš. However, mountainous regions, such as Kopaonik, Zlatibor, and Stara Planina, have become important tourism hubs due to public sector initiatives. In 2023, over 4 million tourists visited Serbia, with more than 2 million foreign tourists (The Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024). The number of domestic tourists is more stable and ranges from 1.5 million to 2 million, while the number of foreign tourists has doubled in the past decade and has grown fivefold in the past twenty years (The Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024). Mountain tourism, rural tourism, and spa and wellness tourism are prominent products contributing to Serbia’s tourism development.

Mountain areas in Serbia attract tourism in winter and summer, offering opportunities such as hiking tours and climbs to high peaks. Other popular sites scattered throughout the country are the many karst caves and canyons, and ski trails generally well-equipped for ski enthusiasts during winter. Surrounding the mountains are dense forests abundant with small and large wildlife, which are suitable for ecotourism, bird watching, and hunting, while mountain rivers and lakes are ideal for fishing.

In the foothills of mountain areas, spas have gained immense potential in the health and wellness industries. Serbia has a wealth of natural springs with both hot and cold mineral water that are used for resorts and wellness hotels. While spas generate a large influx of domestic tourists, foreign tourists are fewer due to the spas’ focus on health and medical treatments. Currently, Vrnjačka Banja, Soko Banja, Bukovička Banja, Banja Koviljača, and Vrdnik are the most visited spa areas due to their luxury accommodation options and developed infrastructure.

Adding to these manifold natural resources are numerous cultural and heritage sites such as ancient Roman and medieval Serbian castles and monasteries. Developing rural, spa, and mountain tourism products from a single point and with a unified vision has huge economic and social potential and is recognised as one of the main goals in the Tourism Development Strategy of the Republic of Serbia.

Serbia’s Hunting Tourism: Tradition, Conservation, and Economic Growth

Rural areas are suitable for hunting, and hunting tourism is an integral part of rural tourism in Serbia. Hunting tourism can also be considered a tool to diversifying rural livelihoods, and it can help against migration and unemployment as it provides income possibilities that allow young people to stay in rural areas. In general, if the income from hunting tourism flows to the local population, it can play a key role in rural development.

Serbia has a long tradition of organised hunting which, together with its natural potential and favourable climate, is a good foundation for sustainable development in the hunting sector. Hunting and hunting tourism are also important segments of managing natural resources, i.e., hunting is used to help regulate the overpopulation of wildlife, which would otherwise lead to habitat degradation (Ponjiger et al., 2015).

Apart from the country’s urban areas, almost all other areas in Serbia are considered hunting grounds. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy, and the Provincial Secretariat (area of Autonomous Province of Vojvodina) have jurisdiction over all matters concerning hunting. Wild game is state property, and hunting grounds are established and given to users for 10 or 20 years.

To ensure the sustainable management and use of wild game, hunting ground users are responsible for creating management plans. With the approval of hunting authorities, each hunting ground user develops a management plan for their 10 or 20-year period. The plan includes an inventory of the current species populations and determines a sustainable level of use. Because this is a prolonged period during which major changes can happen within its inhabitats and game populations, a second hunting plan is produced on a yearly basis. It is based on the annual spring stock survey of game populations, and hunting is prohibited before the annual plan is approved by the authorities.

Main stakeholders, i.e., hunting ground users in Serbia, include public enterprises, hunting associations and clubs, national parks, the Serbian Armed Forces (Ministry of Defence), fisheries, and private hunting grounds. There are 378 hunting grounds and they are mostly managed by hunting clubs that are members of hunting associations (almost 85% – see the Serbian Law on Game and Hunting). These organisations are considered the largest NGOs in the country. Public enterprises manage state-owned forests and forest land, areas that are typically the most developed hunting grounds in terms of resources and management. They are primarily located in mountainous areas and manage mostly big game such as red deer, wild boar, fallow deer, mouflon, and predators, like wolves and bears.

Protected Areas in Serbia

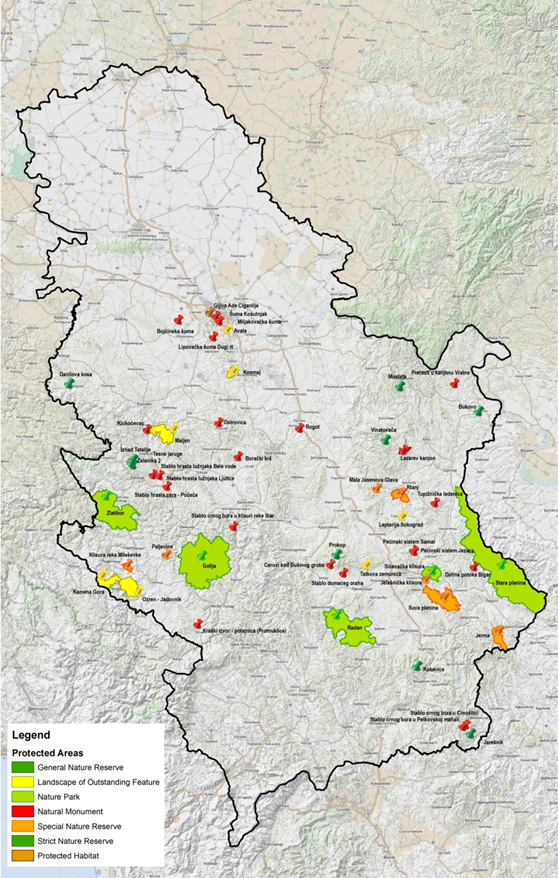

Serbia is characterised by a rich and diverse natural heritage reflected in a wide range of geological, geomorphological, pedological, climatic, hydrological, and biological diversity. A large number of diverse plant and animal species are situated in Serbia, a centre of Europe’s biodiversity. To preserve special natural values and improve their conditions, individual natural ecosystems and some species have been declared as protected natural assets.

Protected areas (PAs) represent an important natural resource and are a vital tool for conserving biological diversity. PAs are spatially defined and legally managed areas for the long-term conservation of nature, related ecosystem services, and cultural values (Dudley, 2008). Managing PAs depends on national legislation that regulates the establishment, management, financing, and use of these areas. The main goals of PAs are to safeguard habitats and species, and to maintain essential ecological processes supporting life and the delivery of ecosystem services (Staccione et al, 2023).

In Serbia, various strategic documents (published in 2005, 2010, and 2012) define the increase of PAs to up to 12% of the territory, while the current coverage of PAs is around 8% (Sekulić et al., 2017; Agency for Nature Conservation). The management of PAs can be divided between the public and private sectors, while the governance of PAs can be divided in “governmental” and “non-governmental” groups (Lausche, 2011). “Governmental” participants are local authorities, agencies, public enterprises (PE) etc., while “non-governmental” participants include individuals, non-governmental organisations, research and educational institutions, religious bodies, enterprises, and private corporations (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2013).

Protected Area Highlight: The Case of Stara Planina

One example of a Serbian PA is Stara Planina, which was declared a nature park and protected area in 1997. The mountain area of the Stara Planina Nature Park (142.219 ha) lies in eastern Serbia within the territory of the municipalities of Zaječar, Knjaževac, Pirot, and Dimitrovgrad. The mountain massif of Stara Planina is marked by the rivers Trgoviški Timok, Beli Timok, Visočica, and Toplodolska, while the mountain massifs are interspersed with streams, rapids, and waterfalls. The area was given the first category of national importance [AE1] [i2], marking the area as valuable for its diversity in flora and fauna as well as geomorphological, geological, hydrological, and hydrogeological characteristics. This categorisation also means that the PA is of highest importance – the management of this protected area is regulated by a separate regulatory body which defines concrete measures and standards.

The Government of the Republic of Serbia delegated the management of this nature park to the public enterprise “Srbijašume.” This public enterprise is responsible for managing 51.2% of all PAs in Serbia and represents one of the country’s main PA management bodies. Ownership of the land is divided between the state (54%) and private owners (46%).

To foster the development of Stara Planina, Srbijasume has established dedicated organisational units, including the Nature Park Stara Planina unit. This unit, supported by the Ministry for Environmental Protection and the Agency for Nature Conservation, oversees organisational and management activities within the park. Collaboration with local communities, various NGOs, and civil society organisations is a key component of the strategy to enhance both environmental and economic conditions in the area. Recognising that parts of this nature park are considered marginalised mountain areas, the Government of the Republic of Serbia issued a decree in 2007 to approve a programme aimed at developing mountain tourism in Stara Planina.

Looking ahead, the park’s development will be further enhanced through the establishment of a Stakeholder Council. This council will bring together diverse stakeholders from both the public and private sectors to contribute to the park’s progress. Currently, the Stakeholder Council is not included in the management plan, as the government has limited such public participation to national parks only.