By Dr Murat Sargıncı (Düzce Üniversitesi)

Connecting the Anatolian Peninsula in western Asia and the Balkan Peninsula in southeast Europe, the Republic of Türkiye has been the bridge between Europe and Asia for over 2,500 years. The country is renowned for its cuisine, rich cultural heritage, intricate architecture, and varied landscapes. Although it spans across an area of 783,356 square kilometres, making it the world’s 36th largest country, Türkiye is only the 107th most inhabited country worldwide. In this blog, we will provide an overview of Türkiye’s topography, geology, and the marginalisation challenges the inhabitants of its mountainous regions face.

A Brief History of Time: The Topography and Geology of Türkiye

Türkiye is a transcontinental country located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. It uniquely borders both the Mediterranean Sea to the south and the Black Sea to the north. Its geographical position results in diverse neighbouring countries. To the west, Turkey shares borders with Greece and Bulgaria. To the east, it borders Georgia, Armenia, and Iran. In the southeast, Turkey shares its borders with Iraq and Syria. The Levantine Sea separates Turkey from Cyprus and serves as a maritime border with Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Egypt. To the west, Turkey has a maritime border with Greece in the Aegean Sea. Along its Black Sea coastline, Turkey shares borders with Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia.

For millions of years, complex tectonic processes have shaped Türkiye’s landscape, resulting in a mountainous and rugged terrain. The region continues to be both seismically and volcanically active. Türkiye is part of the Alpide belt, also known as the Alpine-Himalayan orogenic belt. This significant seismic and tectonic region stretches approximately 15,000 km from the Atlantic Ocean through southern Europe and Asia, encompassing regions such as the Himalayas, the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush, and the Caucasus before reaching Türkiye. The Alpide belt further extends to the west to include the Atlas Mountains and the Alps.

Orogeny describes the process by which the Earth’s crust is folded, compressed, and deformed to create mountain ranges.

The Alpide Belt region, which includes Türkiye, began to take shape during the Cenozoic era starting around 66 million years ago. This period of significant geological transformation was triggered by the tectonic collision of the Eurasian, African, Indian, and Arabian plates. The Alpide Belt is part of a complex system of fault zones that spans the Mediterranean and the Middle East, and it continues to be tectonically active. Rocks in Türkiye are remarkably varied in age. Some date back to the Precambrian era, which began around 4.6 billion years ago, representing some of the Earth’s oldest formations. Others originated in the Mesozoic era, starting approximately 252 million years ago. Still others are relatively young, having been formed by volcanic activity during the Cenozoic era.

Alpine-Himalayan orogenic belt

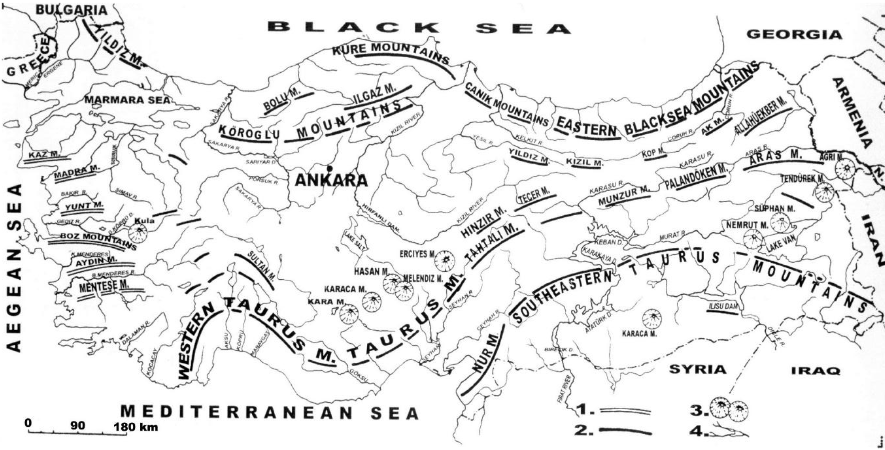

Türkiye is framed by two major orogenic belts: the Northern Anatolian Mountains, situated by the Black Sea in the north, and the Taurus Mountains along the Mediterranean coast in the south. These mountain ranges contribute to the country’s elevated average altitude, which ranges between 1,000 and 1,110 meters. The horst and graben systems are prevalent in western and eastern Anatolia, while other mountainous areas have been dissected by rivers.

Horst and Graben systems (from German, meaning “valley and range”) describes a topographic characteristic formed when the Earth’s crust is pulled apart. This process is also called extension.

Türkiye is home to 12,880 named mountains, covering almost two-thirds of the country. These mountains generally fall into one of three categories: orogenic, tectonic, and volcanic. Significant mountain regions are distributed across western, central, eastern, and southeastern Anatolia. Isolated volcanic cones exceeding 3,000 meters in height are primarily located in the interior and eastern parts of Anatolia. Three peaks in Türkiye reach heights over 4,000 meters: Mount Ararat (Ağrı Mountain) is the tallest at 5,165 meters, followed by Cilo Mountain at 4,134 meters, and Süphan Mountain at 4,058 meters. Other notable peaks include Kaçkar Mountain (3,932 meters), Erciyes Mountain (3,916 meters), and Hasan Mountain (3,253 meters); these are part of the 219 peaks that exceed 3,000 meters in height.

Three types of mountains are common in Türkiye: tectonic, orogenic, and volcanic (Atalay et. al 2018)

A Kaleidoscope of Climates and Ecosystems: Unraveling Türkiye’s Natural Diversity

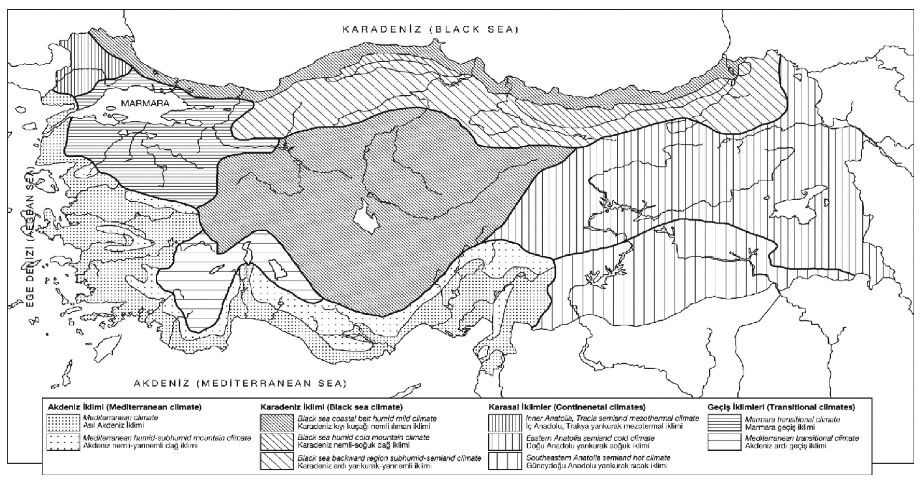

Stretching across two continents, Türkiye serves as a fascinating intersection of diverse climates and ecosystems. Its varied geography and topography contribute to three dominant climates:

- The Black Sea climate pervades the northern part of Anatolia, featuring humid conditions in the lowlands and cold, humid conditions in the highlands.

- The Mediterranean climate is prevalent in the western and southern regions, bringing mild, wet winters and dry, hot summers.

- The continental climate governs the interior and eastern parts, marked by extreme temperature variations, cold winters with long-lasting snow, and hot summers.

The main climates of Türkiye (Atalay 2010)

Türkiye is uniquely positioned at the intersection of the Mediterranean, Euro-Siberian, and Irano-Turanian phytogeographic regions. This distinctive blend gives rise to a rich tapestry of vegetation that varies depending on factors like climate, geology, topography, soil quality, and human influence. For instance, mountains that exceed 1,000 meters along the coast, 1,100 to 1,200 meters in inner Anatolia, and 500 to 600 meters in southeastern Anatolia create unique habitats known as orobiomes.

Türkiye’s geomorphological diversity fosters a wide range of plant life. Its regions are host to multiple ecosystems and ecoregions, ranging from temperate forests and grasslands to scrubs, coniferous forests, and alpine zones. This ecological richness provides habitats for a staggering array of wildlife, including 197 mammal species, 469 bird species, 130 reptile species, 28 amphibian species, 371 freshwater fish species, 440 marine fish species, and approximately 4,000 endemic plant species out of a total of 11,000 plant species.

Phytogeographic regions are regions that present easily distinguishable and regular climates, as well as easily recognizable vegetation and floristic characteristics.

Exploring Türkiye’s Varied Forests: A Mountainous Green Haven

In Türkiye, mountainous regions are often carpeted with forests and alpine grasslands, frequently punctuated by areas of cultivated land. Türkiye boasts approximately 22.9 million hectares of forest, accounting for 29.4% of its total land area. These forests are primarily located in the country’s mountainous regions. As per data from Türkiye’s General Directorate of Forestry (OGM 2020), the composition of these forests includes 32% broadleaf species, 48% coniferous species, and the remaining 20% is a mix of both.

Forests in Türkiye’s high-altitude regions serve as pillars for various interconnected industries. These include wood production, water resources, tourism, and agriculture. They also generate employment opportunities for local communities in these hilly areas.

The country’s mountains, particularly those that ascend beyond 2,000 meters, feature distinct altitudinal vegetation zones, also known as forest belts. For instance, the North Anatolian Mountains offer:

- Broadleaved deciduous forest belts, found at elevations ranging from sea level to 1,200 meters.

- Coniferous forest belts, located between 1,200 and 2,000 meters.

- Alpine grass belts, constituting all vegetation that grows above 2,000 meters.

In the Taurus Mountains, altitudinal vegetation zones are categorized as follows:

- Pinus brutia-maquis zones, extending from sea level up to 1,000 to 1,200 meters.

- Oro-Mediterranean coniferous forests, situated between 800 and 2,000 meters.

- Subalpine zones, which exist above 2,000 meters.

In Inner Anatolia, the altitude-based vegetation breakdown is:

- Steppes, located between 1,000 and 1,200 meters.

- Dry forest zones, found from 1,200 to 2,000 meters.

- Subalpine vegetation, which thrives above 2,000 meters.

These forest belts not only demonstrate Türkiye’s rich ecological diversity but also underscore the integral role of forests in the nation’s economic and environmental well-being.

Mountain and Forest Villages: An Inside Look at Türkiye’s Rural Communities

Türkiye’s rural communities can be broadly categorised into two main groups: forest villagers and mountain villagers. A forest village in Türkiye is specifically defined as a village that contains a forest within its administrative boundaries. With more than 21,000 such villages, their inhabitants collectively represent a diminishing 10% of Türkiye’s total population.

Economic activities in these rural areas are mainly traditional. Residents rely on animal husbandry, low-yield agriculture, and forestry work for their livelihoods. The average income in these communities hovers close to the minimum wage, which is ₺11,450 (equivalent to €400).

Ecoregions of Türkiye (Atalay 2002)

Navigating the Peaks and Valleys: Addressing the Marginalisation of Türkiye’s Mountainous Areas

MARGISTAR is concerned with understanding the challenges of marginalised mountainous areas and working towards solutions to these challenges. Türkiye’s mountainous areas, which constitute approximately 60% of the country’s landmass, grapple with a plethora of challenges ranging from environmental concerns like erosion, floods, and avalanches to systemic issues like underinvestment in public infrastructure, education, and healthcare services. This multi-faceted neglect makes these regions emblematic examples of what scholars refer to as periphery traps, where geographical remoteness combines with systemic neglect to perpetuate cycles of marginalisation.

Periphery traps manifest as a cycle of disenfranchisement: the state allocates fewer resources to these regions due to their perceived low economic productivity and political influence. Consequently, these areas suffer from inadequate infrastructure and social services, which in turn perpetuates their marginal status. The locals are left to bear the brunt of both natural and human-made challenges, ultimately reinforcing the stereotype of mountainous areas being less valuable for national development. This marginalisation extends beyond the lack of public services and includes the underrepresentation of these communities in policy-making processes related to their own regions.

The concept of periphery traps is particularly relevant in Türkiye’s mountainous areas, as neglect is not merely a byproduct of oversight but of systemic issues that cement these regions as ‘low-priority’ in the eyes of policymakers. The absence of targeted strategies for mountain-specific issues only perpetuates the problem, further isolating these regions and their inhabitants.

Therefore, breaking free from periphery traps in Türkiye’s mountainous regions requires a multi-faceted approach. On an administrative level, it would mean carving out distinct governance structures, separate from forest management, to address the unique challenges of mountainous terrain. This would enable the creation of policies that are fine-tuned to local requirements, from mitigating natural hazards to improving healthcare access.

In summary, the dual challenges of natural hazards and systemic neglect represent an urgent call to action. Türkiye’s mountainous regions are not just peripheral areas to be relegated to the margins of national discourse; they are critical landscapes that require focused and equitable attention to both protect and leverage their inherent potential. By directly confronting and overcoming periphery traps, Türkiye can pave the way for a more equitable and sustainable future for all its regions.